Each year, the population of roughly 300,000 inhabitants in Iceland triples with tourists arriving from around the globe seeking breathtaking vistas and itineraries packed with otherworldly tours of lava-fields, glaciers, and waterfalls. In one year, an unprecedented seven hundred asylum seekers arrived on the island nation just south of the Arctic Circle, doubling the previous year’s count.

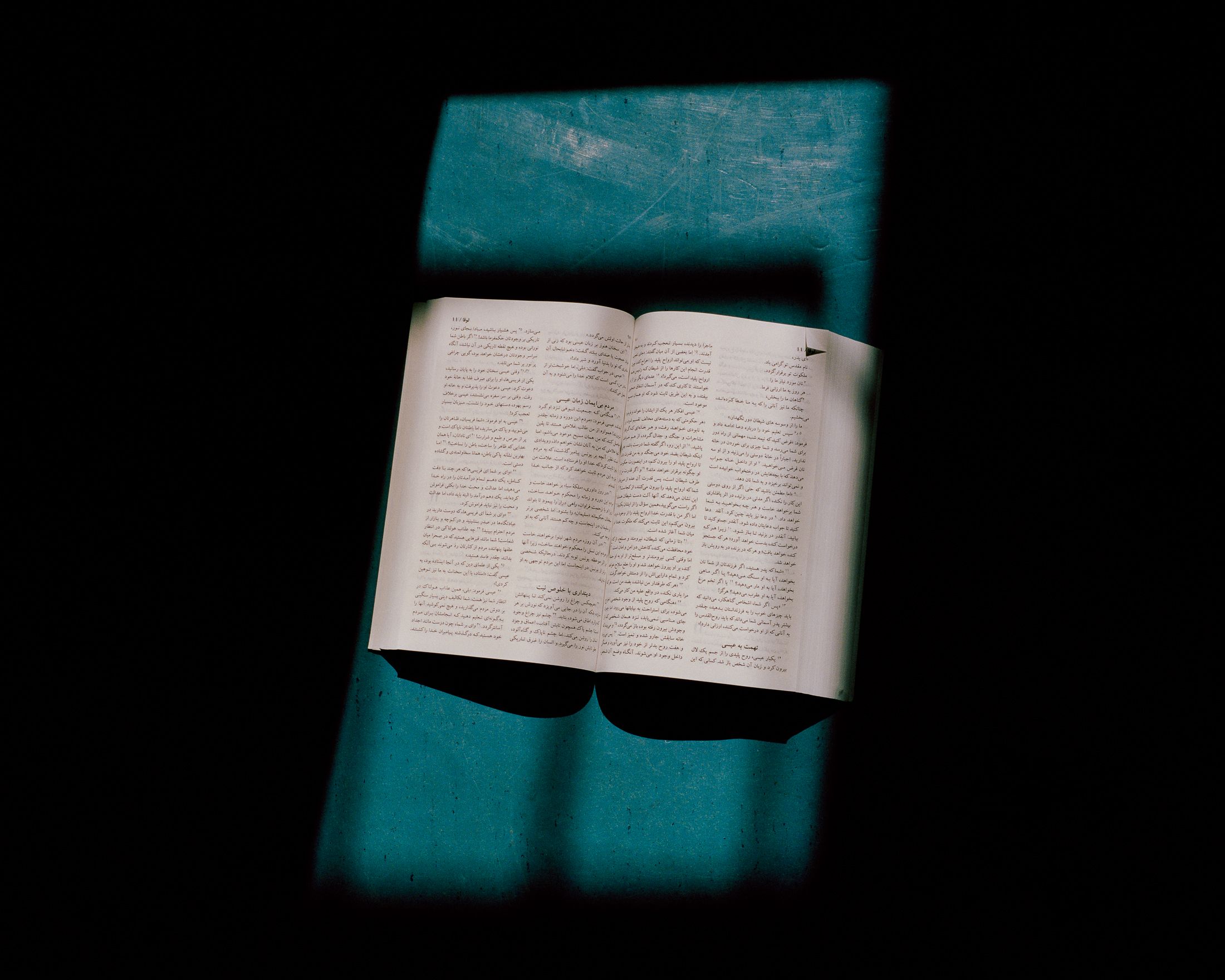

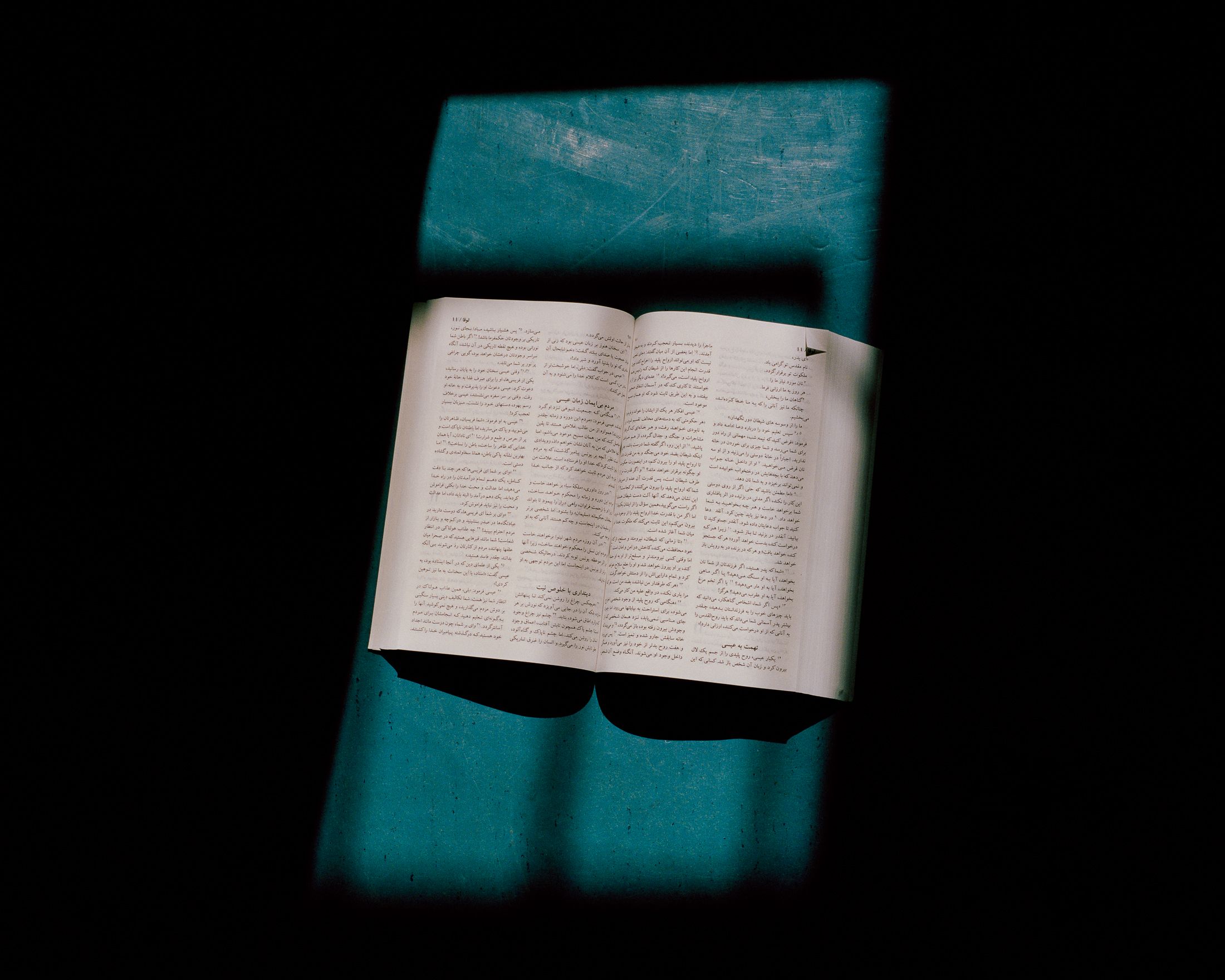

The majority end up in Iceland after their intended destination to the United States, Canada, or the UK is denied. A few sheltered in hostels among tourists and the rest isolated, asylum seekers predominantly from the Balkans and the Middle East wait months before few are granted residency.

How do asylum seekers experience Iceland in limbo? How do resettled refugees adapt and make a home here? Is this paradise or is this purgatory?